An old story in anthropology has it that in the 20s’ a Native Canadian went knocking door-to-door in Ottowa because he wanted to meet the State, who he’d heard so much about. The personhood of states is probably the most powerful modern myth. It’s not just that it lets the different groups using the state as a forwarding address (as it were) get away with so much, as that it encourages everyone to act as if they really live there.

Naturally hypersensitive to the mythology of state power, Carl Schmitt put the problem succinctly: is it any accident that Hobbes chose the giant monster God created and defeated, the Leviathan, as his personification of the state?

Alex Golub conceptualizes the historical arc of this myth succinctly: in the famous old political myths of dragonslaying, God’s defeat of the enemy Leviathan is the original act of sovereignty, allowing him to found his kingdom. After the early modern dethronement of God’s monopoly over the right to violence, the state itself becomes Leviathan.

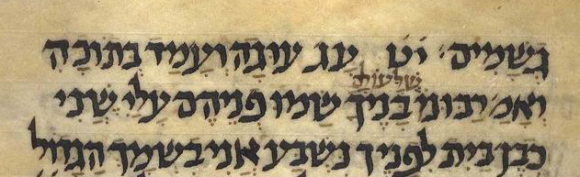

In Iron Age and later Near Eastern myths, God gained the right to rule by defeating the cosmic dragon and sacrificially carving her body–logic that interestingly correlates with cross-cultural patterns of hierarchy and sacrifice. But the myth’s political meaning lay in God’s conferring his powers of sovereignty and violence on his microcosmic correlate, the king. Different versions of this act are narrated in the Babylonian Enūma Elish epic and Psalms 74 and 89. But Aaron Tugendhaft shows that earlier versions–in the diplomatic correspondence of Old Babylonian Mari and the Ugaritic Baal epic–already manipulate or question the neat correspondence between God and his mortal mini-me.

It is this logic that explains a series of strange biblical texts. In both Exodus 32 and the archaic poetry of Psalm 68, a remarkable level of violence is directed at a calf. It is defeated in some of the same ways the war-goddess Anat triumphs against cosmic enemies like Death and the “divine young bull” in Ugaritic myth. Cristiano Grotanelli’s “The Enemy King is a Monster: A Biblical Equation” showed that each is an instance of a larger mythic motif, in which a monstrous non-human creature must be dismembered to protect the cosmos.

Most striking was Grotanelli’s demonstration of how this old myth was transferred to human enemies: in both Judges 3 and 1 Samuel 15 a human king–Eglon of Moab and Agag, King of Amalek, are dismembered with similar cosmic significance. As Dumézil writes, explaining the absence of myths about gods and the presence in early Roman historical writing of themes typical of Indo-European myth,

The myths have been transferred from that great (macrocosmic or divine) world to this (Roman) world, and the protagonists are no longer the gods but great men of Rome who have taken on their characteristic traits.